It was an unusual night. Its blackness hovered like evil cloaks, ready to pounce on the unsuspecting, covering every sparkle of hope with gloom. Occasionally, the fragile silence was pierced by distant gunshots. They ripped through the air like ugba pods when they explode in the harmattan: expected, yet equally startling.

Amanute peeped through the window of the unusual hut they now lived in. The moon seemed too afraid of the dark but a just a few stars stared from the sky, defiant, like eyes of daring children peeping at sacred masquerades from defect openings on a closed door. In the past, even dark nights like this would still be opportunities for stories. The tales will not be by groups soaked by moonlight, instead, all will seat around a bonfire in front of their old hut. They will roast corn and ube as they listened, or on a few occasions, Amaka’s father would roast a portion of the game he killed.

“Ute, Amanute, listen to me!” Father whispered. It was a whisper that felt like a scream and his voice was shaking like that of a beaten child who was trying not to cry. Mother’s face glittered when she faced the hurricane lamp, her two rows of tears shone like the golden sun setting on parallel streams. She had a packed bag as they were headed for the forest hideout again. The war was becoming more intense and the invading warriors had a savage reputation.

“You must do according to all that I instructed” he continued. “We will return on the third Nkwo market day. All you need to survive until we return is in this hut. Please do according to what we instructed.” he hugged them. A restrained teardrop landed on Amanute’s bare back like evaporated precipitation that, because it was held for too long, fell back like a hailstone and not as a raindrop.

“Ute, take care of your sister until we return.” Mother managed to say. Ute nodded, covering her younger sister’s mouth to stop her from crying out.

“Shh…. Ndo!” she comforted Amanute. “They will come back for us soon; ebezila, don’t cry again Ama” she muttered, trying hard not to cry herself as their parents disappeared into the night.

Umunike had not always been a place of fear. It was a place of joyful families that drink from the same stream, buy from the same market and farm together. Without notice, this changed within days. Invaders from the hinterland devoured everything on their path. They wanted more than treasures. They wanted more than territories. They wanted slaves. They swarmed the region like a river that has broken its banks and swept away farmlands, and the crops in these farmlands were people.

It was the second Eke market day and their parents had not returned. Ute was becoming impatient. The days had passed without incidents and in daytime she had wandered around the makeshift hut and went to the road. Amanute remained inside except at night when she went out to ease herself. Crying was of no use, but she often stared at the nzu marks on the mud wall. Her older sister used those marks to count the days and it gave hope of her parents’ return. The gunshots had decreased in intensity and she wondered if the warriors had left the area or the community resistant forces had driven the invaders away.

“I want to eat ofe nsala” Ute said as she came in with fresh oha leaves. “I am tired of roasting yam in embers and eating it with palm oil”

“But papa said we should not make fires that emit much smoke” Amanute countered

“Papa is not here now, besides, I have gone outside this enclave, there are no warriors anywhere”. She brought out a mortar and seeds of achi.

“No, Ute. Mama said we should not pound anything” the little girl objected, trying to restrain her sister.

“You are too fearful Ama. I am much older than you and I know when there is no more danger. Nothing will happen”. She made a fire; because she wanted it to kindle faster, she added dried oil palm fibres and started pounding achi seeds for nsala soup.

Ute was relieved that the baby is weaned and she could resume her trade in fabrics. She had gotten a domestic servant from another part of the country. She did not like the idea of leaving her daughter in the care of a total stranger, but without a mother and a sister, she had no choice. She wondered if the situation would have been different had there been no war, but memories of her village were now vague.

This teenager, Victoria could not be trusted, she thought. She was brought a month before Baby was born and there was something defiant about her seemingly meek disposition. Often, she would be lost in thoughts; besides, she was not fluent in the language of the region. Ute decided that handling her with an iron fist was the best option.

“Hey, you,” she would bark “when you prepare the yam for my child, do not have a taste of the yam itself. Make your own food from the peel. Do you understand?”

“Yes ma” Victoria would reply, staring at the floor. She knew that the period before Baby’s birth was worse. To her, Baby had come like a messenger of hope. Baby was a leke-leke, the cattle egret that gave white finger patches to children when they requested. As a child, she sang a song while flipping her fingers as egrets flew past:

Leke-leke kpambo, nye’m mbo ocha, were oji!

They will be excited when white leukonychia marks would appear, attributing it to the egrets.

“When she cries, try to make her sleep” Ute would repeat.

“Yes ma”. Victoria would not object to any of her instructions.

As usual, when her mistress left, Victoria cooked and fed Baby but that day, Baby did not sleep after eating. When Victoria tried to make something from the yam peels for herself, Baby started crying. To make her sleep, Victoria made up a song. As she sang, she cried too because she was tired, hungry and felt unappreciated.

One day, a neighbour told Ute that there was something unusual about Victoria that she had observed in the past week. She urged Ute to come to her house the following day while pretending to be off to the market. Convinced that Victoria was caught doing something wrong, Ute planned to beat her up and send her away after finding out about the mischief.

Patiently, they waited as Victoria bathed Baby, cooked and fed her. As in recent days, Baby began to cry after eating and Victoria sang:

Ute nwa nnem, Ute nwa nnem o

Dorido!

If only you listened to father

Dorido!

If only you listened to mother

Dorido!

He said we should not light big fires

Dorido!

We promised not to pound the mortar

Dorido!

Ute you made the fire kindle

Dorido!

Ute you pounded with the pestle

Dorido!

The warriors heard and came our way

Dorido!

They came and took us both away

Dorido!

To different places we were sold

Dorido!

For my dear sister I did crave

Dorido!

But now with her I am a slave

Dorido!

For sisters no more know each other

Dorido!

But of this life I won’t regret

Dorido!

If you will sleep on my egret

Dorido!

Ute could not wait for the end of the song. She dashed out of her neighbour’s house screaming and running towards her house, overwhelmed with emotions. She did not notice that her headgear had fallen off or that her wrapper was loosening when she burst into the house just as Victoria laid Baby on the bed.

“Amanute! My sister. My blood!” she screamed as she grabbed and hugged the startled girl.

“Ute nwa nnem!” Victoria replied after recovering from the brief moment of shock. She held on to her older sister, and locked in that embrace, they continued crying. The commotion woke Baby up and she cried too, but her’s was like the sound of an egret who had given two sisters a white patch of hope after long periods of darkness, and their tears became mixed with laughter.

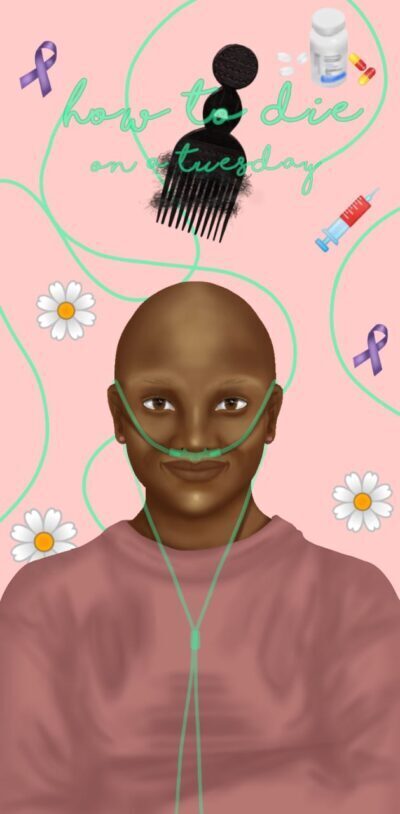

(The story is adapted from an Igbo folktale my mother Eunice Bassey told us as children. The song is an attempt to translate into English what she sang. Photo Credits: Effiong Samuel and Pexels)

Your support is appreciated

I’m sure you enjoyed your experience here and would like to make a kind donation to me. Thank you, in advance!